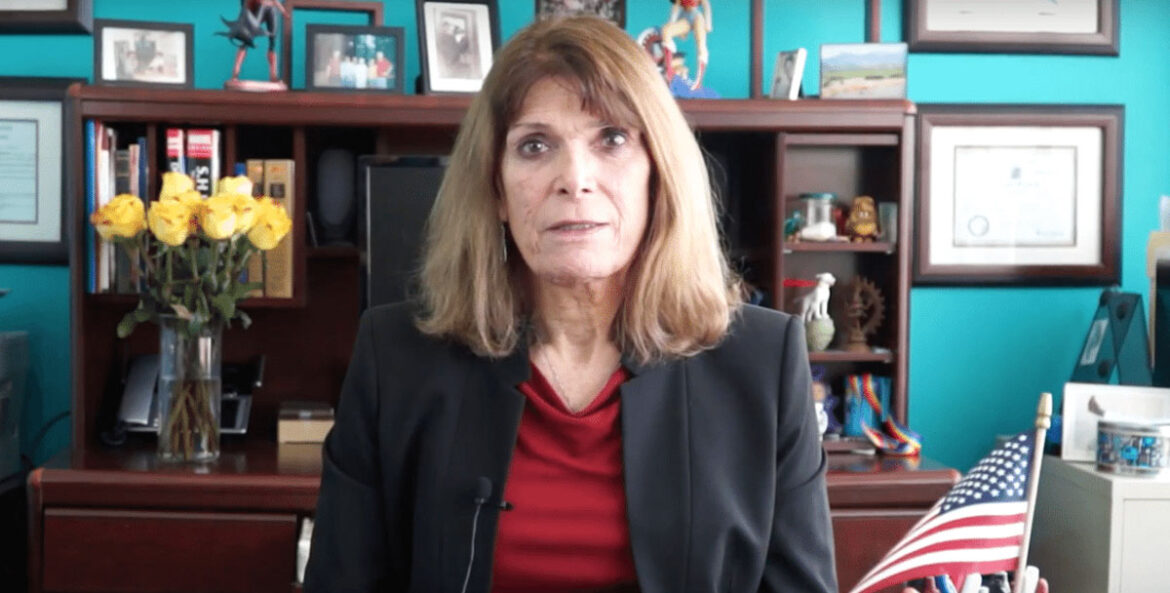

For years, Chicago attorney Jill Rose Quinn has wanted to be a judge.

But for the longest time, Quinn said, she didn’t think she could land a seat on the bench.

“I didn’t think the people would accept a transgender judge,” Quinn told the Tribune.

But on Tuesday night, with most precincts reporting, Quinn declared victory after taking a large lead in her bid to become the Democratic nominee for a Cook County judicial vacancy. If she holds on, that likely would make her the fourth openly transgender judge across the country and the first transgender candidate in Illinois voted into public office.

With 74% of precincts reporting, Quinn had 66% of the vote compared with opponents James Samuel Worley with 18.5% and Wendelin DeLoach with nearly 16%.

“It’s not just a victory for me, it’s a victory for everybody out there who’s marginalized, everybody who’s different, everybody who’s trans,” Quinn said.

If she does win the primary, Quinn will again face the voters in November, though there is no Republican candidate currently vying for the position.

In an earlier interview, Quinn reflected on her historic candidacy.

“There are kids in this country killing themselves because they’re trans and they don’t see a light at the end of the tunnel. They don’t see respect. They don’t see themselves portrayed as being people, not ordinary people, of course, because nobody’s ordinary, but they don’t see how great they can be,” Quinn said. “So I think it’s important for them to see that you can survive, you can prosper, you can go to school, you can study hard. You can make your way, and you can be a judge.”

From a political standpoint, Quinn had several things going for her candidacy: She’s been rated qualified or recommended by 13 different local bar agencies, drew top position on the ballot and has a strong electoral name.

She was also endorsed by the Cook County Democratic Party, which is often pivotal in down-ballot judicial races. Lori Lightfoot, Chicago’s first African American woman and gay mayor, also threw her support to Quinn.

“Jill Rose Quinn has fought for fairness, equality and justice her entire life and her perspective and experience will be invaluable for our courts and our community,” Lightfoot said in her endorsement.

‘Look at everything’

A native New Yorker, Quinn grew up in Queens and attended State University of New York at Binghamton for college. Quinn, 65, was the youngest of four siblings.

For a time after college, she worked as a community organizer in Texas then moved to Des Moines, Iowa. In 1979, Quinn moved to Chicago and worked as a food program specialist for the Department of Agriculture. She applied to John Marshall Law School in 1980.

Growing up during the civil rights era, Quinn said she idolized Martin Luther King Jr. and former United States Attorney General Bobby Kennedy.

“My concept was, I want to stand up to the establishment, and my father said, ‘You’ll go broke,’” Quinn said. “But I still wanted to do it, and that’s what’s inspired me.”

She also was inspired to pursue a career in law by the Marvel comic book character Daredevil, a ninja who was blinded as a child but who also practices law. In her office, Quinn keeps a Daredevil portrait on the wall.

In 1983, Quinn graduated and passed the bar, then took a job in Bloomington, Illinois. Because of the town’s mid-size, Quinn said she got a good opportunity to work in a lot of different areas of the law.

There, Quinn said she did her first and only jury trial, a felony possession of stolen goods case where her client was accused of selling a stolen radio.

The client was convicted, Quinn said, but between the finding and sentencing, Quinn filed a post-trial motion arguing that prosecutors hadn’t proven that the value of the goods met the bar for a felony. The judge agreed, knocking it down to a misdemeanor, Quinn said.

“It taught me you have to look at everything,” Quinn said. “You have to make sure you examine every element of the state’s case. You have to hold them to that standard. You have to make them prove everything.”

Her legal practice has been “in helping people solve problems,” Quinn said.

Sign up for The Spin to get the top stories in politics delivered to your inbox weekday afternoons.

“What I’ve really liked is working with an entire family because you do a good job in a real estate closing for a family, then they come back to you when they need their wills done,” Quinn said. “They come back to you when their child has a traffic ticket or when their grandfather has to go into a nursing home and needs a power of attorney. That’s what I’ve really liked about my practice.

“I’ve gotten to know a lot of people,” Quinn added. “I’ve gotten to be part of people’s lives.”

‘To thine own self be true’

From the age of 4, Quinn said, she knew she was a girl but suppressed it.

“Trans people spend a lot of time, especially in my generation, just trying to please everybody else and suppress who they are,” Quinn said.

Quinn transitioned in 2002, she said.

“I realized that people who loved me would still love me,” Quinn added. “People who weren’t gonna love me were never going to love me.”

But life after the transition hasn’t always been easy, Quinn said. It caused some rifts with loved ones. And in federal court one day, Quinn recalled, a judge continually called her “sir.”

I was unmistakably dressed as a woman, you know — makeup and heels and a nice tan suit like President Obama wore,” Quinn said. “And he just kept on calling me ‘sir,’ and I just kept on biting my lip harder and harder ’cause I didn’t want him to do anything bad to my client because I mouthed off at him.”

Quinn worked up a speech she was going to give the next time someone bothered her for her gender, she said, but it wound up being unnecessary as people treated her well. Even the offending judge, who Quinn declined to name, has been better.

Another judge told her, “Counsel, you’ve gotta be happy inside your own skin.”

“Everybody can learn,” Quinn said. “Everybody can be educated. … I’m optimistic about human nature.”

Still, it wasn’t until 2010 that the United States had its first transgender judge.

In 2010, Houston’s then-Mayor Annise Parker, who is openly gay, appointed Phyllis Frye to be the first transgender judge in the United States. Parker recalled there were some protests from the “far right,” but for the most part, it wasn’t controversial.

There are currently three openly trans judges in the United States, and two of them were appointed. Across the United States, there are only 25 elected trans officials, according to a database kept by the LGBTQ Victory Fund.

But still, experts and advocates said the trans community has made great progress in the years since. There’s been “a sea change in the visibility of the trans community,” Parker said.

“If people are going to have faith in our system, they need to see themselves on the bench,” she added. “It changes hearts and minds.”

Locally, Quinn said she’s been treated with respect by Chicago-area politicians as she sought their support.

Illinois Senate President Don Harmon, who chairs the Cook County Democratic Party’s judicial slating committee, noted that social attitudes on LGBTQ issues have changed dramatically since he first took office in 2003.

“It has really been a remarkable transformation culturally,” Harmon said. “There are very few issues where the public perception changes so rapidly over the course of a decade or two.”

Full article: www.chicagotribune.com